Welcome to the first article of our suspension series! In this first edition, we’ll take you through the basic function of mountain bike suspension and demystify the common features and adjustments on offer. In future articles, we’ll delve into how to set-up your suspension and then delve into some maintenance tips to ensure you get the most out of your bike’s suspension.

Suspension technology has advanced dramatically over the years and will continue to do so, therefore the sheer wealth of information available is seemingly infinite. It certainly takes an expert to understand the intricacies of suspension, but we are here to explain the basic need-to-knows for all mountain bikers.

Modern mountain bikes are nearly all equipped with suspension. The purpose of suspension is to dampen the roughness of the terrain, providing the rider with a smoother, more controlled ride. A bike with just front suspension (a suspension fork) is referred to as a hardtail, a bike with both front and rear suspension is referred to as a dual-suspension, or full-suspension bike and a bike without any suspension at all is known as a rigid mountain bike.

Front Suspension

The front suspension, or fork, takes a large majority of the rider’s weight, as mountain biking sees the rider often riding with more weight over the front of the bike. Most mountain bike forks will feature a degree of adjustability, ranging from firm to plush, as well as adjustability in the amount of travel for some models.

Working like telescopic tubes, a fork is made up of stanchion tubes (the ‘inner tubes’) that slide in and out of the fork lowers (the outer tubes) and joined with a brace (lower arch). The front wheel is attached to the fork lowers, while the stanchions are attached to the headtube of a bike frame, via the fork steerer.

There are many aspects that make a suspension fork structurally sound, and typically more expensive forks are better equipped to resist flex than cheaper options. There are a number of ways that brands achieve this, the most popular of which is through using larger diameter stanchion tubes and specific oversized axles to hold the front wheel in place, known as thru-axles.

A suspension fork is based around a spring and a damper - yet it is far from that simple! On lower-end models or the occasional gravity-focused fork, a metal coil spring features.

An air spring is the more popular spring type on more expensive forks, which sees the spring rate controlled by air pressure. The degree of adjustability and tuning is near infinite in an air spring.

The damper is there to both counter and assist the spring. Without the damper, the fork would compress and then uncontrollably return. Here, the damper acts to control how quickly the spring returns, along with helping to control how easily the spring compresses. For example, most modern forks offer the option to close the damper, providing a lockout to the suspension.

The vast majority of suspension forks keep the spring and damper separate, with the spring often in the left stanchion and the damper in the right.

Rear Suspension

Rear suspension is found on dual-suspension mountain bikes only. You might hear these referred to as ‘full-sus’ or ‘duallies’ in mountain bike vernacular. As the terrain becomes more challenging, a rear shock will absorb the bigger impacts and keep your wheel tracking on the trail, allowing more control and confidence for the rider.

Much of what is applicable to front suspension is also found on rear suspension including the adjustments such as damping and air pressure, however, the shock must be treated in its own context as the setup will be different to the front.

The rear shock sits under the rider usually somewhere between the front and rear triangles. The shock is contained within a pivot system, which uses linkages to allow the shock to move within the frame. Different bike brands have different pivot configurations, but all modern designs do more or less the same thing.

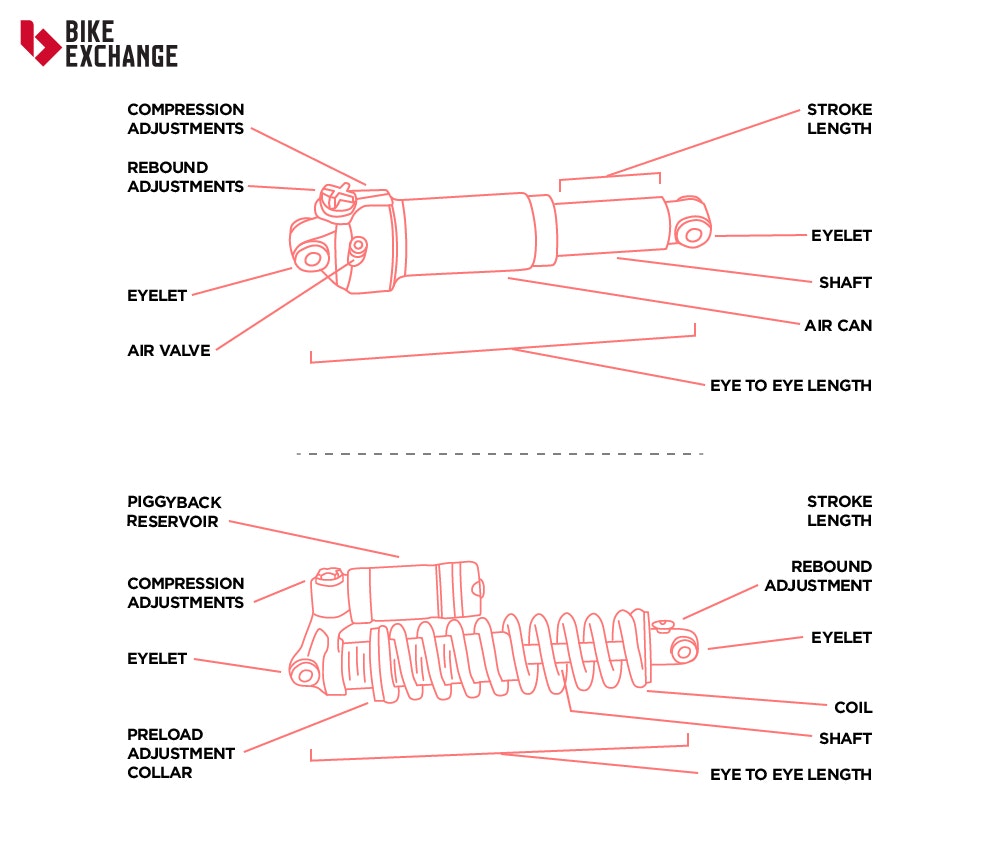

Rear shocks consist of two telescopic tubes which slide into each other which compress under load, housed by the "shock body’’. As with a front suspension, rear shocks can be air or coil sprung, come in different shaft diameters and feature a large amount of tuning and adjustability to suit rider's demands.

Coil sprung shocks are still very commonly used on heavy duty downhill and enduro mountain bikes, as they tend to handle heat better, but come at the cost of less fine-tuning adjustment options and added weight.

Coil shocks offer a more linear progression and finer tuning, but come at a small weight penalty

Rear shocks are commonly sized specifically to the frame, with the size, stroke length and dampening options specific for different frame and linkage systems. Be aware if you are wanting to change or upgrade your shock that it will fit your frame and you have the right mounting hardware.

Although most suspension brands offer a similar range of adjustments options, the mechanism to do so will vary. The best way to know what dial to turn or button to push is by looking up your shock on the brand website and reading its instructions manuals, trust us, they are very user-friendly and well laid out with easy to read graphics and instructions.

Different Suspension for Different Disciplines

Different riding disciplines place different demands on the bike and the rider, so the suspension will vary accordingly, with the amount of ‘travel’ - which is the amount the suspension is able to compress (more travel = more give = more impact absorption).

See our table for an explanation of the amount of travel and the corresponding type of bike.

| Riding Style | Terrain | Travel in mm | Travel in inches | Stanchion Diameter | Recommended Sag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross Country | Smoother trails, good for going uphill | 100-120mm | 4 - 5" | 30 - 32mm | 15-25% |

| Trail/All Mountain | Mixed terrain, including more trail features but still lots of pedalling | 120-150mm | 5 - 6" | 34mm | 20-30% |

| Enduro | Gravity based trails, bigger drops, rugged root or rock gardens | 150-180mm | 6 - 7" | 36 - 38mm | 25-30% |

| Downhill | Steep, rough technical gravity trails, large rocks, drops and jumps | 180-200mm | 7 - 10" | 40mm | 25-35% |

Suspension Adjustment and Function Options

When it comes to front and/or rear suspension, the functions and adjustment options are often very similar. Below we outline what these functions are.

- Air pressure: 'Air-suspension' equipped suspension use a Schrader valve to allow air to be pumped in using a special shock pump. On a fork, this valve can be found on the top of the left fork crown (above the stanchions) or sometimes on the bottom of the lowers. On a rear shock, the valve is normally visible at the top of the shock. Bikes will often come with a manual to help you choose the right amount of air pressure for your bike and weight.

However, these should only be used as a guide, and suspension sag (defined below) remains the proven method for a perfect setup.

Correct pressure adjustment is critical to a safe, controlled ride. Too much pressure and the suspension will not be active to critical hits and will ride harshly while offering poor traction. Too little pressure and the suspension will ‘bottom out’ on larger impacts, causing a hard stop to your suspension when you need it most, and potentially leading to component damage.

Fox suspension has the air-pressure valve located on the top of the crown

Spring Preload: Where air pressure is used to adjust an air spring, preload is the equivalent function for a coil suspension. Here, a small range of adjustment allows fine tuning of how hard or soft the equipped spring is. This feature is available on both front forks and rear shocks using coil springs, but it’s important to remember that unlike the infinite adjustment that air springs offer, coil spring preload adjustment is a small range, and a change in spring is required for bigger adjustments.

Sag: The correct air pressure or coil spring choice is determined by measuring sag, which is how much the suspension compresses simply under the rider's weight when sat on the bike, this is with no further input from the rider or the trail. When measuring sag, it’s important to do so with your riding gear, so if you typically wear a hydration pack, be sure to wear it here.

For most air suspension, the shaft of the shock or fork will likely have numbers listed in percentages so you can adjust the air pressure to achieve correct sag, by adding or removing air in small increments using a shock pump.

If such markings are not available, the use of an o-ring (if fitted) or tied rubber band will allow you to measure the sag with a ruler. The sag percentage is based on the total travel available, something that is often reflected in the total visible fork stanchion or shock shaft length.

As a general rule, aim for 15-20% sag in cross-country bikes, enduro bikes around 25% and downhill bikes around 30% sag. We will cover setting up sag properly in a later article, in the meantime, your suspension will have a set-up manual available online that can help.

Getting sag dialled is a priority as it dictates the balance of your suspension, and we are going to suggest balance on a mountain bike is quite important!

- Damping: Without damping, forks would simply mimic a pogo-stick and see riders blowing through all the suspension at the sign of any big hit, or conversely, getting bounced and bucked around with any change in terrain.

The damping system regulates the rate at which the fork compresses and rebounds back from compression by way of a controlled restricting or releasing of oil.

Compression Damping: Controls how quickly the fork absorbs impact, so it determines more or less how much of your travel will be used at the given time. Compression damping is often split into two types: Low-speed and High-speed.

High-speed compression: Controls fork performance during bigger hits, landings, and square-edged bumps, and helps prevent the suspension from blowing through all the travel and ‘bottoming-out’.

Low-speed compression: Controls fork performance during rider weight shifts, G-outs, and other slow inputs, by holding the suspension higher up in its stroke range. This helps counteract pedal bob when climbing. It’s the low-speed compression that’s typically adjusted when using a lockout control.

Rebound Damping: Controls how quickly the suspension returns from being compressed. More rebound damping produces a slower returning fork, less rebound dampening produces suspension that returns faster. The goal with rebound is to find a balance where it absorbs consecutive impacts but not too quickly that it forces the wheels to lose traction and feel like a pogo stick! Rebound is recommended to be set after setting your sag. Suspension set up is deserving a whole other article, so stay tuned later in the series for our guide to setting up your suspension.

Lockout: Many forks come equipped with either a fork or handlebar-mounted suspension lockout. This essentially gives the option to turn the suspension on and off, or provide some level between. For example, more expensive suspension models typically offer settings that range from ‘open’ (suspension remains fully active), ‘firm’ (some damper resistance, good for smoother off-road climbs) and ‘closed’ (fully locked out).

Ultimately, after some experimentation, the damping settings will help you feel more controlled and smoother on the trail.

What You Get When You Pay More

The Kashima coating used by Fox makes for a smoother and better-performing suspension parts

When deciding between bikes, typically more expensive bikes will be equipped with more expensive suspension, but what does that mean?

Suspension savvy mechanics will tell you that cheaper suspension will simply not have the same quality internals, the implications being that the internals break down under repeated usage due to the heat and friction generated from riding. This results in oil degradation, leading to loss of performance and function.

Also, more expensive suspension components are built to higher standards and often with more complex designs, so not only are tolerances tighter and parts smoother, but often the function is more advanced. So if you are rider likely to push the bike to its limits, you will want your suspension to match your riding ambitions.

In summary, a more expensive suspension will get you:

Better ride feel, best described as plusher and lighter

More adjustability to suit the riders style, terrain and preferences

More reliable and consistent performance due to better build quality

Lighter weight, stronger materials, specifically the internals like cartridges, seals

Stanchions coated with a microscopic coating to fill in imperfections on the metal surface and provide a smoother feel, for example, Fox Kashima coat or Rockshox Diamond coat.

Stiffer construction that allows your wheels (and bike) to better follow the terrain.

Popular Brands

Most bikes will come standard with either Fox or RockShoxSuspension. However, there are many other brands on the market with some more boutique than others, or just specialising in rear shocks only, you may come across the following;

- Marzocchi

- Manitou

- MRP

- Ohlins

- DVO

- Cane Creek

- BOS

- Push

Looking After Your Suspension

A suspension system will require regular servicing and cleaning, as well as proper cleaning and care at home. Our next series will look at what is involved in a suspension set-up, how to upgrade and why with first-hand advice from suspension experts from Cyclinic and MTBSuspension.

Thanks to The Ride Cycles for helping out with the creation of this article. Check out our comprehensive Guide to Buying a Mountain Bike for more information.